The State of the Data Economy

by Nick Jordan, on April 24, 2017

As data has become more important the data toolchain hasn't kept up

The amount of data in the world today is staggering and companies are eager to take advantage of that data to make strategic decisions, such as who, when and how they market their offerings.

For example, back in 2012, as Apple was launching the iPhone 5 to replace the iPhone 4S, investment bank, Piper Jaffray, wanted to know how the new phone was being received by consumers. Apple is notoriously tight-lipped about projected and actual sales of their flagship product, so they couldn’t expect any information from the Cupertino tech giant.

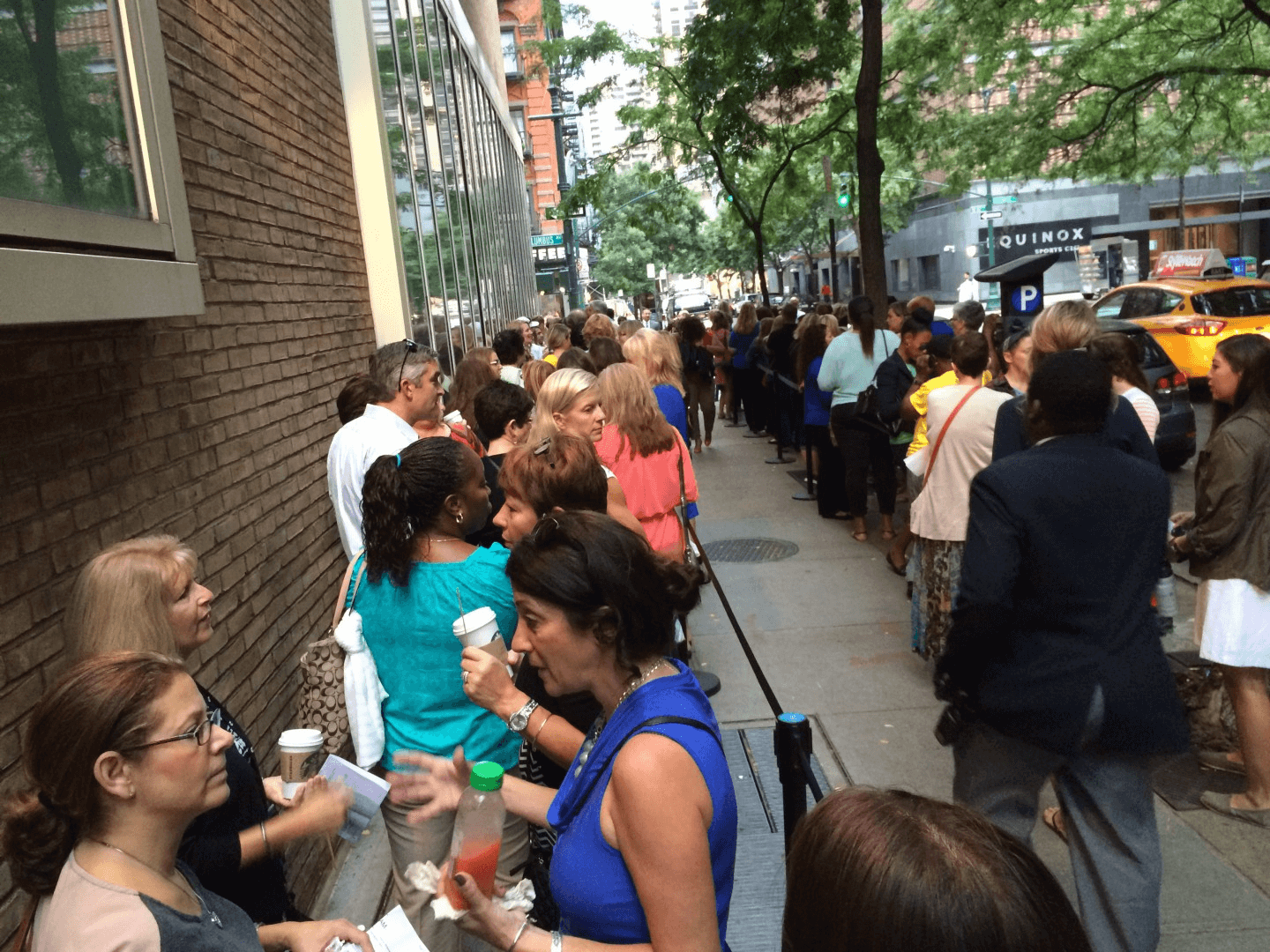

Instead, managing director Gene Munster sent Jaffray staffers to count the number of people standing in line at Apple Stores around the country to see how the number compared to the year before when the 4S was being released.

The news was good for Apple. The number of people standing in line was up 68% at Apple’s 5th Avenue location. The total number of people counted over the two launches? 1235.

The two points I find most interesting about the Piper Jaffray story are:

- They didn’t have the data they needed to run their analysis

- To get the data, they implemented an incredibly inefficient, unscalable, and inaccurate solution.

Sending humans to manually count large numbers of other humans is a labor-intensive process. Apple has hundreds of retail locations globally. Sending someone to each one isn’t possible and, even if it was, you’d still have the problem of not counting people purchasing phones at non-Apple Store retailers. The obvious solution is to try to measure at stores that are representative of the entire population. Any pollster can tell you this is easier said than done.

Piper Jaffray, an investment bank with over $8 billion of assets under management, needed information but they didn’t have the data they required to efficiently model iPhone sales. So, despite their extensive resources, they had to resort to an unsustainable process to get the data.

This is an often-overlooked reality in the era of ubiquitous “big data.”

Stories like this aren’t uncommon in today’s data obsessed businesses. From retailers using predictive analytics to inform their merchandising strategy to manufacturers using data to reduce waste, improve quality and increase yield.

Of course, companies that want to leverage data to run their business more effectively are acutely aware they don’t always have the data to execute on that strategy. This has led to the birth of a market that operates mostly behind the scenes where companies buy, sell, and trade data sets. These new markets have the potential to change how we do business if they can make raw data more accessible and usable for the companies that need it.

The data value exchange

Companies are starting to view data as an asset, like any physical asset. The challenge with data is that it’s a new type of asset that lacks a history of best practices, tools, and expertise around it. As companies look at ways of transacting around this asset they run in a number of inefficiencies that are not easily overcome.

Discovery: Finding data to use

Let’s start by looking at buyers.

First we should note that data acquisition is happening across a variety of industries, use cases, and job functions within an organization. It is hard to define an “average” case. That being said there are some commonalities.

Typically, it starts within an organization’s business development team. Someone is charged with finding the data — a task that’s easier said than done. Most business development professionals begin by making a list of everyone that they think might have the data. Ironically, it’s not a data-driven process. It involves brainstorming based on existing relationships and hunches.

In this example, let’s say the list has 100 potential companies. When contacted, most of these companies likely don’t have the data the buyer is looking for or they don’t have the data at the scale the buyer needs. Depending on the quality of hunches in this first step, the list may quickly drop to 20 opportunities.

These 20 companies present a new challenge: Just because they have the data doesn’t mean they want to sell it.

This is what I refer to as a sell-side discovery problem. For most companies, monetizing their data assets isn’t their core business. When they get the opportunity to sell their data, they don’t necessarily have the operational bandwidth or expertise to fully realize the scope of the opportunity.

For buyers, this looks like 75% of potential sellers opting not to sell their data because:

- They have no way to quantify the size of the opportunity, or

- They want to avoid distractions them from their core business.

For the seller, it’s a missed opportunity to monetize a core asset.

Pricing: Understanding the value of data

If we could make a match between buyer and seller, the next step in the process is negotiating the price of the data and which data can be purchased.

Because the data economy largely exists behind closed doors, there isn’t an efficient mechanism to price data. And, unlike fixed assets, the typical rules of supply and demand don’t apply. Negotiations begin with the seller saying they want a huge sum of money, and the buyer counters that they can’t afford much.

This gap exists, at least partially, because these deals tend to happen against huge data sets. If the parties were negotiating the price for the data on a data point by data point basis, it would be much easier to agree to terms.

The challenge becomes how to efficiently negotiate across millions, or even billions, of individual data points. It’s a problem that’s been solved in other disciplines, such as high-frequency trading in financial markets and advertising exchanges by creating high-volume, biddable marketplaces.

The fact that these data sets are transacted in bulk also leads to an optimization problem for buyers. The problem shows up when the buyer realizes they’re buying the same data multiple times.

It’s like a collector buying baseball cards by the pack. They purchase a bulk set of cards; usually ten per pack. When they purchase multiple packs, there’s a good chance they’ll end up with duplicate cards.

The same applies to buying data: The buyer is getting less return for their investment because duplicate data adds no incremental value.

Delivery: Sending and receiving a virtual asset

If the parties can overcome the inefficiencies of discovery and and the difficulty of pricing the data, they graduate to the challenge of how to send and receive the data.

There’s no real standard for how parties deliver data and this creates a host of issues:

- Every data transaction deal results in a net new integration that needs to be done. The added work often limits the number of deals either side is willing to do.

- Prioritizing the work on both sides can take a long time. There have been instances where the actual integration is completed over a year after the data contracts were signed.

- Completing the integration is really only just the beginning. Data integrations are notorious for how fragile they are. That fragility leads to long-term maintenance costs that are often poorly understood by the organizations involved.

The sooner we establish a centralized platform based on best practices for sourcing, valuing and integrating data being purchased, the sooner we’ll truly benefit from the data that’s available for use.

As the data economy begins to flourish, a variety of solutions have popped up to meet the needs on the buy-side and sell-side. They each have their pros and cons, but none fully meets the needs of organizations trying to develop a robust data strategy.

The most obvious way that data deals are done is through point-to-point relationships. This is where a buyer and a seller agree to deal terms and pass data directly amongst themselves.

- Most notably, these deals require an incredible amount of human capital to sign, so they’re hard to scale. To put it in perspective a single data deal likely involves resources on both sides from business development, product management, engineering, legal, and finance.

- Direct deals also don’t allow for optimization by either the buyer or seller. Each side is locked into whatever terms were negotiated upfront. The seller can’t efficiently increase yield through competition and the buyer can’t easily tune the data they’re buying.

Data Economy 2.0

Airlines long ago figured out that running their systems point-to-point from every city wasn’t scalable. They addressed this by creating a hub and spoke model to create efficiencies in how they get passengers from point A to point B.

Though point-to-point deals have downsides, it’s worth noting they often give buyers access to data sets that their competitors can’t obtain. This is a side effect of the general inefficiency of direct data deals but it’s not exclusive to this type of deal.

Data Arbitrage / Networks

As the inefficiency of direct deals became obvious, a number of data networks began to pop up.

Data networks generally act as an intermediary between the buyer and seller. They pay the data owners a flat fee for their data and then resell it with a significant markup. Most of these businesses justify their exorbitant fees by applying their “secret sauce” between the seller and the buyer. In many cases that marketed value-add is either nonexistent or not worth the mark up applied by the middle man.

This model eliminates some of the inefficiencies of the direct deal but they come with their own issues. Essentially, the intermediary creates an impenetrable wall between the buyer and the seller. This lack of visibility leads to incentive alignment issues. In other words, these networks are incentivized toward their own bottom line, as opposed to the value or utility of the data. Put even more simply these networks are doing data arbitrage.

Arbitrage is a sign that the market is inefficient, which is a side effect of the market being in its infancy or hasn’t fully matured. But the data economy is hitting an inflection point where we’re seeing tools that address some of these issues and those tools are pushing the market to the next level of maturation.

Data Co-ops

Some companies join co-ops to get the use of additional data from other businesses. Data co-ops allow members to tap into data contributed by other member companies. The intent is to enable members to expand their reach and scale their efforts beyond the limitations of their internal data sets. The problem is it’s not an efficient way to transact data. Member companies don’t know up-front what they’re getting or if it will meet their needs.

Where do we go from here?

The inherent and ongoing problems with buying and selling data highlights a critical need in the industry. Various data transaction models have attempted to solve these issues, but there isn’t a standout solution. The industry needs a solution that addresses buy and sell challenges to create an ROI-positive experience for both data owners and data consumers. It’s the only way to stay competitive in the data economy.

By Nick Jordan

CEO, Narrative